C64 Macro State Machine

In this post we will see how asi64’s (Racket’s) macro system can massively reduce the amount of 6502 assembly code you have to write, beyond what a typical macro assembler can achieve.

State Machines

I am currently writing my first little game for the C64. In it, the player’s sprite has fairly complex movement behaviour which is represented by a state machine that has no less than 13 different states. In order to transition between the states, the player uses some combination of joystick controls, or something outside such as collision detection forces a state change.

In this post we will concentrate on state changes from the joystick. Programming these state machines can be tricky due to the amount of different possible transitions from one state to another and the priority in which they are checked. To show this we will look at a reduced and simplified view using 3 of the 13 states and the interactions between them.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

The above code defines some constants for the three different states, a location to store the current state, and some masks used to detect which buttons on the joysticks are pressed when reading the joystick register.

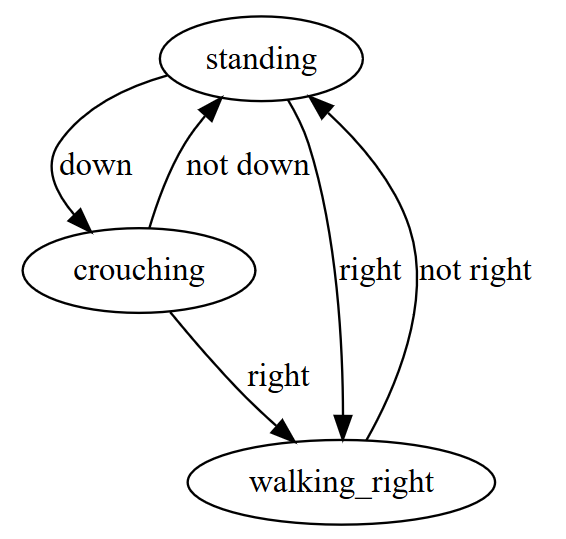

The states that are defined represent the player standing still, walking to the right, and crouching. A graph of these transitions looks like this :

Even in this simple example, complexity rears its head. Notice that you cannot transition from walking right into a crouch, since I don’t want the player to enter that state accidentally as they are walking along if they happen to pull the joystick down and right at the same time. Additionally, there has to be some inverse logic for button presses to make some transitions, for example, when walking right, NOT holding right puts you back into the standing state. You can imagine with 13 states this can start to get very complex.

Programming this in 6502 asm is not particularly difficult, it’s just long, boring and very repetitive which in turns makes it a chore to change and maintain (more on the ineffeciency of this approach in the closing thoughts…) Here’s an example for the standing state :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

:update-machine

ldy current-state ; load current state

cpy @state-standing ; is it the standing state?

bne next-state+ ; if not then go to the next check...

lda $dc00 ; load the joystick state

tax ; preserve it in X so we can look at it again later..

and @joy-right ; test joystick (1 is not pressed, 0 is pressed)

bne skip+ ; if not, move to next joystick check

ldx @state-walking-right

jsr change-state- ; call the function that changes the state

rts ; early exit from function

:skip

txa ; reload the joy data

; repeat all the above the for next direction

and @joy-down

bne skip+

ldx @tstate-crouching

jsr change-state-

:skip

rts ; return from function

:next-state

cpy @state-walking-right

; .... repeat all the code for each state and each transition

|

You can see this is going to extremely long winded with 13 different states each with multiple transitions, sometimes with more complex trigger logic (eg, combinations of joystick button being pressed, things not being pressed and so on).

In addition to this, since this is the update function for the machine, this is also where logic will take place that affects the game depending on the state, e.g. the walking right section needs to actually update the player’s X co-ordinate.

The final salt in the wound is that some state transitions need to execute some logic after the transition actually takes effect, for example resetting some variables or switching on / off some additional sprites.

Whilst I enjoy writing assembly code, I don’t so much enjoy maintaining a monster like this. I takes forever to try changes or introduce new states and it is very easy to introduce subtle, silly bugs that you don’t notice until later.

Macros to the resuce!

Racket’s amazing macro system can help us out here. Wherever you see replication of code, macros are ready to lend you a helping hand. In this example we won’t even see any of the really fancy stuff racket can do, just basic macros.

The way I like to write macros is to first write down the syntax I would like to be able to write, then work backwards from that point to make it happen. Let’s keep it simple to start with, and forget about having to execute game logic and pre-transition logic. In fact let’s also forget about the actual machine states and just concentrate of the repetitve bit in the middle which is the checking of joystick states.

As an inital concept, let’s say it would be nice to write this :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

:update-machine

ldy current-state

cpy @state-standing

bne next-state+

(generate-joy-transitions

([joy-right #t state-walking-right]

[joy-down #t state-crouching]))

rts

:next-state

; .....

|

The macro generate-joy-transitions will take a list of lists, each inner list has three elements. The first is the bit pattern to test against the joystick register, the second is a boolean that indicates if the button should be tested against being pressed or NOT being pressed, and finally the last part is the target state.

Let’s have a frst go at writing it :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

(define-syntax-parser generate-joy-transitions

[(_ ([test is-pressed? target] ...))

#'{lda $dc00 ; load joystick register

tax ; preserve it in x

{

and @test ; test bits

; ?? how do we perform the branch?

ldx @target ; perform state transition

jsr change-state-

rts ; exit function

:skip

txa ; restore joytsick data

} ...

} ; repeat ...

])

|

This is not a terrible first attempt, we simply pattern match on the inner list, extracting the parameters into the names test is-pressed? and target, the ellipsis ... that follows tells racket that any amount of these lists may appear here.

The first two asm instructions are generated only once - the inner section which is wrapped in a nested 6502 block using { } is repeated for each set of arguments thanks to the ... that follows the block.

A problem remains though - after the AND test, we must use a different branch instruction depending on if we are checking that the button was pressed or not pressed via the is-pressed? parameter (bne and beq respectively). How can we do this? We can’t simply replace is-pressed? in the pattern match with #t and then replicate the pattern and macro output with another case for #f, because that would mean ALL of the provided arguments would have to be same, which is no good.

Macros in yer macros..

Likely there are many ways to skin this cat - Racket generally likes you to be declarative about these things, so one way is to simply define another macro that takes care of it.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

(define-syntax-parser joy-branch

[(_ #t) #'{bne skip+}]

[(_ #f) #'{beq skip+}])

(define-syntax-parser generate-joy-transitions

[(_ ([test is-pressed? target] ...))

#'{lda $dc00

tax

{

and @test

(joy-branch is-presed?) ; call the other macro here

ldx @target

jsr change-state-

rts

:skip

txa

} ... }

])

|

Cool, now it works as expected. Infact, since we haven’t told Racket to expect any particular types (eg, expressions, integers) as the parameters, it is totally possible to pass expressions into test and target, which is very handy if you wanted for example to test a combined bitmask for more than one button at once:

1 2 |

(generate-joy-transitions

([(bitwise-ior joy-right joy-down) #t some-state]))

|

Very nice! We basically got that for free. For the final piece of this section we wished to be able to execute some arbitary code after the transition has finished. However, we dont always want to do this, and Racket has just the answer by allowing us to put in an optional parameter that will be defaulted to an empty block if not supplied.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

Now we can write

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

(generate-joy-transitions

([joy-right #t state-walking-right]

[joy-down #t state-crouching

{

; some asm code...

}]))

|

Of course, a 6502 block is inlined in the above example, but it could equally call a function that generates some code, calls another macro, or whatever.

Macros in yer macros in yer macros …

The final icing on the cake is to get rid of the state machine branching logic completely. To do this we need to :

- Create essentially the

switchstatement for each state - Allow some arbitary code be executed

- Check all joystick transitions as above

So, what we want to be able to write is :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

(generate-state-machine

([state-standing

{ }

([joy-right #t state-walking-right]

[joy-left #t state-walking-left]

[joy-down #t state-crouching

{ some code ... }])]

[state-walking-right

{

; move sprite right

inc $d000

inc $d000

}

([joy-left #t state-walking-left]

[joy-right #f state-standing])]

; more cases ...

))

|

Following the patterns above this pretty much writes itself:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

(define-syntax-parser generate-state-machine

[(_ ([state-number

update-code

joy-cases] ...))

#'{

{

ldy current-state ;load current state

cpy @state-number

bne next-state+

update-code ; insert update code here

;call the joystick macro with the cases

(generate-joy-transitions joy-cases)

:next-state

} ...

}])

|

And we are done.

Closing Thoughts

Macros are a super powerful way to help introduce new syntax over the top of the assembler, and this is really just scratching the surface of it.

This example is kept simple, it has some obvious problems such as the “switch” statement uses branching instructions that can only go +/– 127 bytes and it will break if there is too much code between the branch and the label. It also has to check each state until it finds what it is looking for - a nicer way would be to use a lookup table and jump to the correct address, which is totally possible with a little more macrology …

Happy assembling!

Additional Edit!

Since I posted this earlier today, I have changed the switch-statement type affair into a much more effecient lookup table, and I thought it might be interesting to show how it works, since it uses the assembler’s open architecture by directly calling into some of the functionality it provides rather than using the assembler syntax.

The idea is to do the following

- Load the current state number

- Using the number as an index, lookup the low address byte where the code for that state lives. Store this number somewhere

- Repeat to lookup the high address byte, store it next to the low byte

- Use the indirect jump op-code to jump to this address.

In order to do this we will have to know the location of each state’s code that we assemble and put their locations into lookup tables split by their low and high bytes. There are a few ways to do this, the easiest is to label each section of state code, then later extract the address details into lookup tabes. Here’s how it looks :

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 |

(define-syntax-parser generate-state-machine

[(_ ([state-number

update-code

joy-cases] ...))

#'{

ldx tc-state ; load current state

lda state-machine-lo: x ; use lookup table and setup

sta jump-vector-lo+ ; 16 bit address pointer

lda state-machine-hi: x

sta jump-vector-hi+

jmpi jump-vector-lo: ; jump to target state

; write out the states

{

;set jump location

(set-jump-source-current (format "state~a" state-number))

update-code

(generate-joy-transitions joy-cases)

rts

} ...

(define jump-labels

(~>>

(list state-number ...)

(map (λ (n) (format "state~a" n)))

(map (λ (n) (find-closest-label n (here) '-)))))

:state-machine-lo

(write-values (map lo-byte jump-labels))

:state-machine-hi

(write-values (map hi-byte jump-labels))

:jump-vector-lo (data $FF)

:jump-vector-hi (data $FF)

}])

|

The first lines of code load in the current state, perfom the indexed lookups into the tables and store the address in the jump-vector. Then, the code jumps via this vector and begins executing the code for the current state.

The code that writes out the states directly calls the internal assembler function to add a label set-jump-source-current, and it names the label state-n where n is the number of the state it is processing.

At the bottom of the macro, we take ALL the numbers together (list state-number ... ) re-format them into the label names, call another internal assembler function that locates a label from a given location find-closest-label and finally extracts the low or high bytes from it. These are then written out as lookup data.

Finally, the last two lines label a couple of bytes to use as a jump vector that is written to from the jumping logic.

This is really cool! Now the state machine is much more effecient and has no worries about branching limitations. Most importantly, you can add and remove states withouht ever having to worry about moving loads of code and numbers around, and making far less mistakes because of it.